From Okinawa to Central Park

by Luchia Meihua Lee

"... a world without art and happiness resembles a

nursery without laughter." - Hendrik Van Loon (1882-1944)

In this ATW, I would like to bring your attention to a unique

artist from Okinawa, next door to Taiwan in the first island chain.

https://conta.cc/2GNdoHn

image: The Hudson, Upstate New York. 80 x 58 inches, four-panel folding screen, pigment and dye print on silk, wood frames, 2011

Hiroshi Jashiki is a native of Okinawa, the former kingdom

of Ryukyu [1], an outpost of culture sticking up out of the Pacific Ocean.

Okinawa is rich in indigenous and mainland Japanese culture mingled with

oceanic themes and American influence.

From Okinawa to Central Park

Okinawan treasures include exquisite handcrafted textiles,

amazing ceramics, heart-touching sanshin melodies, and shisas (lion guardians).

All the historical splendor and local culture mingle with the contemporary

sense which has already moved into original daily gourmet food. The landscape -

from sand to mountains - is never far removed from the dominant influence of

the sea.

Hiroshi Jashiki lives and works in New York, although he was

born and grew up in Okinawa, Japan. He uses imagery from many sources but

especially from Okinawa and New York City. Because of his use of textile

software technologies and carefully controlled color and composition, the

original photographs from which he starts are no longer visible at the finished

stage. Influenced both by Okinawa native hand weaving and modern digital

textile design methods, "Jashiki takes his inspiration from nature. The

colors he uses for dyes are sophisticated and delicate, giving his work a minimal

sparseness that at the same time is dreamy." [2] image: Water, 40 x 60 inches, silk noren, 2017

"The foundation of Jashiki's career was the indigenous,

skilled hand weaving which he encountered on the Okinawan islands. His horizons

were expanded first by formally studying art and then by embarking on a career

in the New York fashion industry as a textile designer." [3.]

Jashiki comments: "Kasuri is a weaving technique. It

basically is a yarn dye tie-dye (warp and weft yarns are tie-dyed beforehand)

weaving. It is also known as "Ikat". What makes Okinawan Kasuri

unique is its geometric patterns. I fell in love with it when I took a weaving

class in college, and it was my weaving teacher's specialty as well. It is a time-consuming

technique, but with my extensive textile design experience in the US, I am able

to use a double weave technique to achieve the modern Okinawan Kasuri look

(though my designs are kind of ultra-modern compared to traditional ones).

"As for dyes, in Okinawa they still use many natural

dyes (including Okinawa indigo). Natural dyes are beautiful but susceptible to

UV light. I use chemical dyed yarn for my tapestry for this reason. "

Kasuri to contemporary metropolitan scenes

If we say that a "fiberscape" is a weaving that

encapsulates a landscape in fiber, then Hiroshi Jashiki captures landscape and

unwinds it in a fiber painting phantasmagoria. As with phenomenology, Jashiki's

art can be deconstructed in terms of "parts and wholes, identity in

manifolds, and presence and absence." [4] At the same time, as an artist

he exhibits reverence for conversations about nature, the land, minimalism,

abstraction, and Zen practice in a contemporary technological presentation.

Jashiki contains all these conversations because "everything in the

outside universe can be represented in the inside, and the representations are,

according to Beckett, either "virtual, or actual, or virtual rising into

actual, or actual falling into virtual." [5] Many of Jashiki's works are

ultimately finished either by paint brush splashes in breaking water or by a parallel

but unfixed and unfixable line in a calm sea fading into the horizon reflecting

rich, sophisticated blues or reds. The intercourse effected by fabric threads

ranges within (warp and weft) longitude and latitude, and overlaps to create

vision. The traditional Okinawa dyeing and knitting effects in his new weaving

pieces are accomplished by computerized Jacquard hand weaving in conjunction

with back-lighting to make multi-layered textile landscape scenes that rise to

shining when lit by strong sunlight.

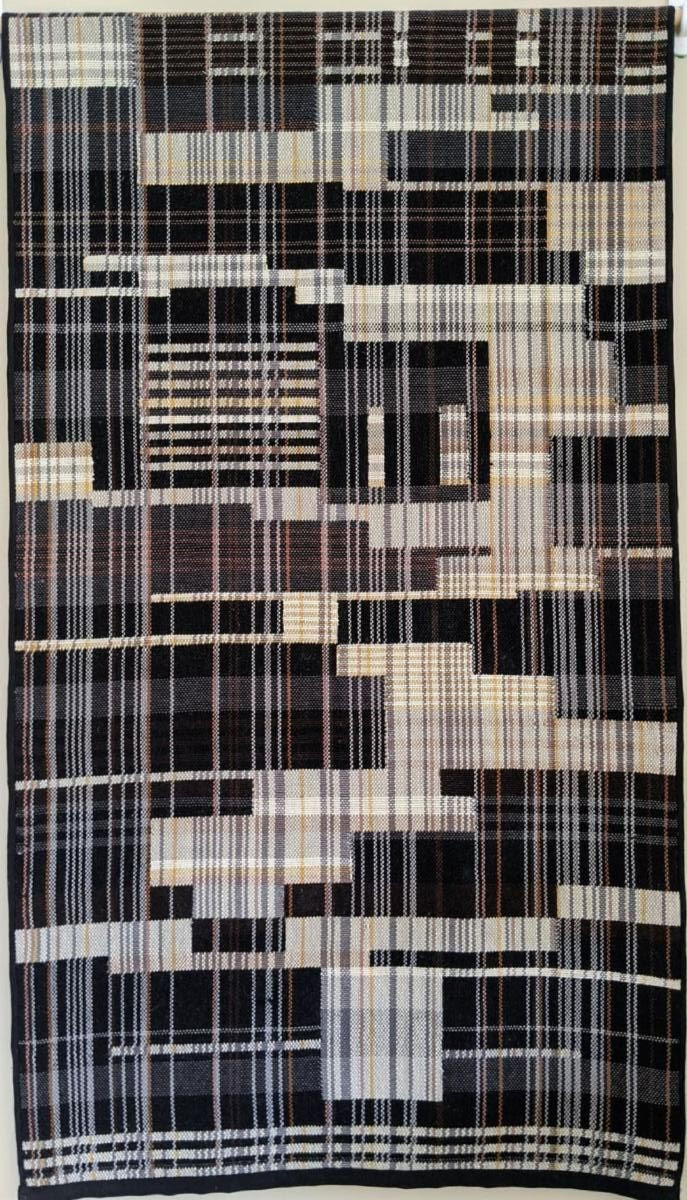

(the image is half of the entire tapestry) The artist used a Western double-weave technique in place of Kasuri methods inreacting to networks of information and communication of the city.Both Okinawan legends and vibrations of daily activity in

New York City's Central Park enchant Jashiki. For the "Central Park tea

ceremony screen" series, he adapted the silk screen process for art,

making tea screens suitable for the serene concentration of the tea ceremony,

or for ethereal evocations of change. The large size of these silk screens

brings meaningful natural scenery indoors, making landscape an indispensable

part of the room. Central Park play an important role in Jashiki's mindset, as

he explains

"The northern part of Central Park is the most

interesting and enchanting. It may sound odd, but the only time I get nostalgic

is when I’m strolling in the park. Though I’m not sentimental by nature, I

can’t help feeling that I’m actually in Okinawa. If the park vegetation is

slightly unruly or the color of the pond is moss green, it definitely is

Okinawa. And in the winter, melting ice on the pond reflecting the bare trees

is a Japanese esthetic."

As documented in the Okinawa Prefectural Museum in Naha,

Okinawa's principal city, from 1429 to 1609 the Kingdom of Ryukyu thrived on

the Okinawan Islands. Ryukyu was a center for maritime trade between China,

Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and the countries of East and South East Asia. This

special status persisted even after Japan closed down virtually all other

trade.

Like the exuberant vibration of the music of Sanshin, the

tea screen binds fine art and daily life in a unity rooted simultaneously in

ancient imagery and contemporary world. Jashiki's fabric paintings enlist

classic imagery to imply modern and contemporary simplicity.

Blue Plaid hangs on the north wall of the lobby

of the Hilton Okinawa, which was built right beside the Pacific Ocean. Red

Plaid graces the south side of the lobby. Because of oversize

windows, Red Plaid shimmers with the orange resonance of the

reflection of the sunrise and sunset, while Blue Plaid harmonizes

with daytime views of the Pacific. The compositions are simple, and the artist

has evinced a high degree of skill in blending of idealization and realistic

sternness to achieve an abstract likeness that expresses not only the indomitable

air expected of an accomplished artist, but also those more personal traits

that reverence his family home. It is nowadays increasingly difficult to

distinguish national boundaries. In Hampton, the dazzling

outrageous waves crest and break on the silk canvas. And in the silk

screens Nice, South France and Untitled, Jashiki

realizes phenomena by a stray shaft of ocean and sky light coming through sheer

veil spilled over the silk screen. The restriction to horizontal or vertical

strokes in Blue Plaid and Red Plaid echoes

the image edge. As a result, his work has greater richness of texture and

shading than could be achieved simply by depth of color and suggests the

interplay of gradient and linearity. Western abstraction has been achieved with

Zen-like simplicity, by means of a masterly use of materials. Jashiki’s art is

the supreme rebuttal to Greenberg’s dismissal that Minimal Art is “too much a

feat of ideation and not anything else.” [6]

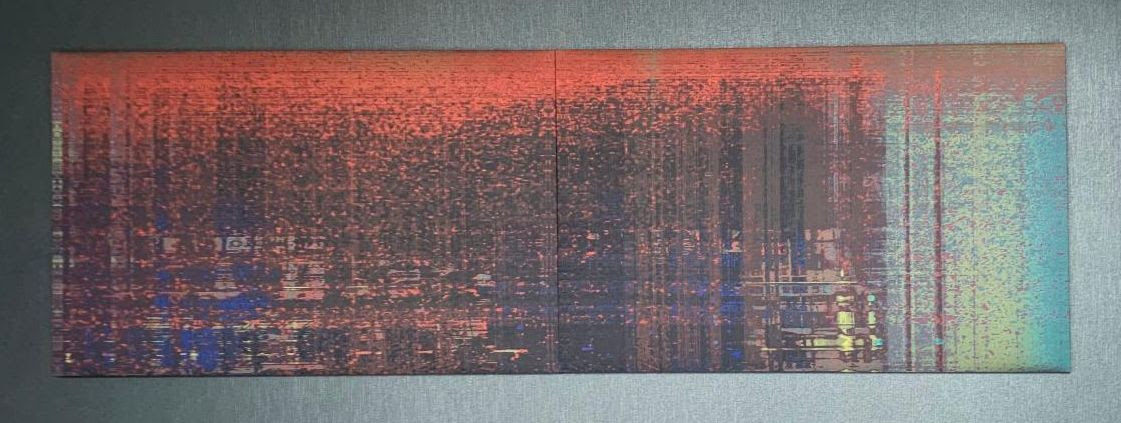

images: Red Plaid, 57 x130 inches, pigment on the canvas, 2011

Minimal painting still has all the elements of composition

and structure and creativity and form according to Frank Stella. [7] In

Jashiki's work, "nothing is minimal about ... the craftmanship, inspiration,

and aesthetic stimulation" as John Perrault points out. [8] Whether in

painting, curtain, tryptic, or screen, Jashiki creates both realistic and

highly abstract motifs to covey a romantic feeling. as the artist notes "

[in fashion] there are so many contrasts and uses of those elements

coexist harmoniously. Eastern/Western, traditional/modern, fine art/commercial

design, hand work/high tech (CAD). The interplay of those elements is my

chronicle as well."

However ardently some partisans may advocate for Okinawan

independence, it has been almost half a century since the United States

formally returned the islands to Japanese control, and Japanese influence is

pervasive there. So, it is quite natural that Jashiki's art should celebrate

Japanese aesthetic ideals such as pristine elegance, painstaking craftmanship,

and celebration of nature's beauty.

American appreciation for Japanese culture long pre-dated

the battle of Okinawa and the Second World War. During the 1860s, the initial

period of "Japan Fever" sparked the US to ratify a trade and

friendship treaty with Japan. The 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia exposed the

broad public to Japanese artifacts and spurred industrial promotion of Japan.

"[A]appreciation of Japanese art encompassed both its own aesthetic merits

and its effect on the industrial revolution" [9] and later in the 19th century

more and more Americans more became familiar with Japanese culture and objects.

In fact, as usual, art appreciation preceded the elevation of Japonisme to “a

truly worldwide worldwide status [through] commercial negotiations (sometimes

among several nations), trade agreements and political machinations and

pressure, combined with the personal energy of two generations of

entrepreneurs" [10]

Unlike the French and English passion for Japanese art, the

initial American enthusiasm for Japanese art owed very little to the wood

print, the photograph, or indeed any works on paper [11]. However, in due

course the American craze for Japanese art objects would become more comprehensive.

Jashiki's work is eclectic in topic, falls into many

different categories, and has evolved beyond any particular philosophical

school. It raises craftmanship to the highest level of art. It participated in

the artistic revival of naturalism, and on the silk print, in turn was impacted

by it. Its meaning and structure acted as a stimulus in his personal drive

toward abstraction.

Notes:

*The first island chain refers to the first chain of major

archipelagos out from the East Asian continental mainland coast. Principally

composed of the Kuril Islands, Japanese Archipelago, Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan

(Formosa), the northern Philippines, and Borneo; from the Kamchatka Peninsula

to the Malay Peninsula. *https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_island_chain

**Rewoven: innovative Fiber Art exhibition

catalogue, TAAC, QCC Art Gallery/CUNY, Godwin Ternbach Museum/CUNY, Kaohsiung Museum

of Fine Art, 2017

[1] The Kingdom of Ryukyu existed from 1429 to 1879; it lost

its independence in 1609 after invasion and subsequent domination by Japan, but

Okinawa was not formally absorbed into Japan until 1879. Thus Okinawans had

been Japanese citizens for barely two generations at the outbreak of World War

II. Nevertheless, in the wake of the battle of Okinawa, the United States

severed Okinawa from Japan after the war and occupied it until 1972. [By

comparison, the American occupation of mainland Japan ended in 1952.] During

this period, American bases utilized as much as 80% of the available land in

Okinawa, the American dollar was the official currency, and vehicular traffic

drove on the right. Currently, there are approximately 25,000 American troops

stationed in 30 bases in Okinawa.

[2] Lee et al, catalogue for Rewoven:

Innovative Fiber Art, QCC Art Gallery/CUNY, Godwin Ternbach

museum/CUNY, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Art, Taiwanese American Arts

Council, 2017, p 110

[3] Ibid.

[4] Robert Sokolowski, Introduction to Phenomenology,

Cambridge University Press, 2000, p.4

[5] Ibid, p. 11

[6] Edward Strickland, Minimalism: Origins,

Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1993, p. 273

[7] Gregory Battcock, ed. Minimal Art,

University of California Press, 1968, p. 180

[8] "Minimal Abstract by John Perreault",

in Gregory Battcock, ed. Minimal Art, University of California

Press, 1968, p. 260

[9] Julia Meech and Gabriel Weisberg, Japonisme

Comes to America, Harry Abrams Inc., New York, 1990, p.17

[10] Ibid, p. 18

[11] Ibid, p. 19

More

information about artist Hiroshi

Jashiki

Internet Profiles

https://hiroshijashiki.com/

Hiroshi Jashiki

Hiroshi Jashiki is a textile artist who was born in Okinawa.

Growing up in this semi-tropical, amazingly diverse island, his interests in

arts and crafts, and international cultural sense came naturally from his

earliest years.

Jashiki went to Ryukyu University in Okinawa where he

studied arts and traditional crafts including hand woven textiles. Later he

studied at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where he

received his MFA in Fiber Art. Jashiki moved to NY and worked in the

fashion industry as a textile designer for 20 years. In 2006, he became an

independent textile artist creating original print and handwoven pieces for

shows and for public spaces.

In his print work, Jashiki employs textile software as a

tool to create images inspired by nature, Okinawa, and New York City among

other influences. He has exhibited his work in US and Japan; some of the

galleries include Cranbrook Art Museum in Michigan, Renaissance Fine Art,

Nippon Club New York, and in Japan, Shibatacho Gallery Osaka, Kasagi Gallery

Kamakura, Okinawa Contemporary Art Museum, and Atos Gallery.

His latest project is a series of prints for Rihga Royal

Gran Hotel, Hilton Okinawa Chatan Resort, Blossom Naha in Okinawa, Courtyard

Marriott Tokyo Station, and Ashiya Bay Court club Hotel Resort in Kobe, Japan.

Hiroshi Jashiki artist statement

My encounter with local textile was an affair. Although

Okinawan textiles play an important role in Okinawan History, my meeting with

“it” was not until my late teens, specifically on one afternoon in Shuri High

School. I was helping textile major students get ready for their graduate

exhibition. I noticed first the smell of Ryukyu Indigo, and then the softness

of handspun silk, and last modern geometric patterns. The experience was

emotional. “Falling in love” maybe. Not like lovers but like a baby meeting its

mother for the first time. I felt warm and protected just by touching the

fabric. The affair left an imprint on me.

A recent boom in tourism has pushed developers to

carelessly build luxury condos, high-end hotels and malls in Okinawa.

Eventually booms bust; you can’t count on them in the long run. The

flipside--we gain little or nothing culturally. Okinawans pay less attention to

their cultural assets in terms of “old” under the circumstances. The Islands

have abundant cultural assets: textiles, pottery, music, dance, and more.

They’re beautiful, shape our identity and make us different from the rest of

Japan and the world. Cultural assets also are a power to share with the global

community. And eventually they will help the Okinawan economy. There is no “old

“or “new” in cultural assets. They are timeless. They just need close

attention, nurturing, and helping hands to evolve with time. That is the reason

I use textile medium and an Okinawan aesthetic in my art.

Okinawa (Ryukyu Kingdom) - historical foundation for

modern culture

The Government of the Ryukyu Islands was the self-government

of native Okinawans during the American occupation of Okinawa. It was created

by proclamation of the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands

on April 1, 1952 and was abolished on May 14, 1972 when Okinawa was returned to

Japan, in accordance with the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement. The government

consisted of an executive branch, a legislative branch, and a judicial branch.

Members of legislature were elected. The legislature made its own laws, and

often had conflicts with USCAR, who could overrule their

decisions.(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Ryukyu_Islands)

Original E-blast and link

https://conta.cc/2GNdoHn

"... a world without art and happiness resembles a nursery without laughter." - Hendrik Van Loon (1882-1944)

In this ATW, we'd like to bring your attention to a unique artist from Okinawa, next door to Taiwan in the first island chain.* We hope you do not begrudge praise and admiration. |

|

Hiroshi Jashiki is a native of Okinawa, the former kingdom of Ryukyu [1], an outpost of culture sticking up out of the Pacific Ocean. Okinawa is rich in indigenous and mainland Japanese culture mingled with oceanic themes and American influence. |

|

Iced pond, Central Park, 86.5 x 34 inches, pigment print on silk habotai, Tea ceremony screen, 2014 |

|

The Hudson, Upstate New York. 80 x 58 inches, four-panel folding screen, pigment and dye print on silk, wood frames, 2011 |

|

Forsythia, Central Park, 79 x 27 inches, pigment print on silk habotai, Tea ceremony screen, 2014 |

|

From Okinawa to Central Park |

|

Okinawan treasures include exquisite handcrafted textiles, amazing ceramics, heart-touching sanshin melodies, and shisas (lion guardians). All the historical splendor and local culture mingle with the contemporary sense which has already moved into original daily gourmet food. The landscape - from sand to mountains - is never far removed from the dominant influence of the sea. Hiroshi Jashiki lives and works in New York, although he was born and grew up in Okinawa, Japan. He uses imagery from many sources but especially from Okinawa and New York City. Because of his use of textile software technologies and carefully controlled color and composition, the original photographs from which he starts are no longer visible at the finished stage. Influenced both by Okinawa native hand weaving and modern digital textile design methods, "Jashiki takes his inspiration from nature. The colors he uses for dyes are sophisticated and delicate, giving his work a minimal sparseness that at the same time is dreamy." [2] "The foundation of Jashiki's career was the indigenous, skilled hand weaving which he encountered on the Okinawan islands. His horizons were expanded first by formally studying art and then by embarking on a career in the New York fashion industry as a textile designer." [3.] |

|

Ginza, triptych 129 x 40, 40 x 40, and 40 x 40 inches Jacquard weaving, 2020. Installed at the restaurant in the AC Hotel Marriott Ginza, Tokyo.

Ginza exemplifies exquisite craftmanship with refined sensibility and taste. Constructed for a site overlooking the hotel reception room, its new levels of inventiveness convey sophisticated aesthetic concepts.

|

|

Jashiki comments: "Kasuri is a weaving technique. It basically is a yarn dye tie-dye (warp and weft yarns are tie-dyed beforehand) weaving. It is also known as "Ikat". What makes Okinawan Kasuri unique is its geometric patterns. I fell in love with it when I took a weaving class in college, and it was my weaving teacher's specialty as well. It is a time-consuming technique, but with my extensive textile design experience in the US, I am able to use a double weave technique to achieve the modern Okinawan Kasuri look (though my designs are kind of ultra-modern compared to traditional ones).

"As for dyes, in Okinawa they still use many natural dyes (including Okinawa indigo). Natural dyes are beautiful but susceptible to UV light. I use chemical dyed yarn for my tapestry for this reason. " |

|

Ancient map of the city of Naha, image from the exhibition at Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum. From the time of the Independent Ryukyu Kingdom to the modern era, Okinawa has undergone vast changes as a result of trends in the policies of Japan, America and other factors on the international stage. |

| The sanshin (三線, literally "three strings") is an Okinawan musical instrument. it consists of a snakeskin-covered body, neck and three strings. Image from the Okinawa Prefectural Museum, photo by LL |

| Hiroshi Jashiki, untitled, 30 x 56 inches, double weave, wool, 2019, courtesy of the artist

The artist used traditional Okinawan weaving methods to create this handicraft artistic work.

|

|

Hampton, 35.5 x 19 inches, pigment print on double-layered silk, 2012 |

| Clouds, 15 x 15 inches, double-layered silk, private collection, 2015 |

|

Kasuri to contemporary metropolitan scenes |

|

If we say that a "fiberscape" is a weaving that encapsulates a landscape in fiber, then Hiroshi Jashiki captures landscape and unwinds it in a fiber painting phantasmagoria. As with phenomenology, Jashiki's art can be deconstructed in terms of "parts and wholes, identity in manifolds, and presence and absence." [4] At the same time, as an artist he exhibits reverence for conversations about nature, the land, minimalism, abstraction, and Zen practice in a contemporary technological presentation. Jashiki contains all these conversations because "everything in the outside universe can be represented in the inside, and the representations are, according to Beckett, either "virtual, or actual, or virtual rising into actual, or actual falling into virtual." [5] Many of Jashiki's works are ultimately finished either by paint brush splashes in breaking water or by a parallel but unfixed and unfixable line in a calm sea fading into the horizon reflecting rich, sophisticated blues or reds. The intercourse effected by fabric threads ranges within (warp and weft) longitude and latitude, and overlaps to create vision. The traditional Okinawa dyeing and knitting effects in his new weaving pieces are accomplished by computerized Jacquard hand weaving in conjunction with back-lighting to make multi-layered textile landscape scenes that rise to shining when lit by strong sunlight.

image upper right: Empire State, 56 x 32 inches, double weave, cotton, 2019 (the image is half of the entire tapestry) The artist used a Western double-weave technique in place of Kasuri methods in reacting to networks of information and communication of the city.

Both Okinawan legends and vibrations of daily activity in New York City's Central Park enchant Jashiki. For the "Central Park tea ceremony screen" series, he adapted the silk screen process for art, making tea screens suitable for the serene concentration of the tea ceremony, or for ethereal evocations of change. The large size of these silk screens brings meaningful natural scenery indoors, making landscape an indispensable part of the room. Central Park play an important role in Jashiki's mindset, as he explains

"The northern part of Central Park is the most interesting and enchanting. It may sound odd, but the only time I get nostalgic is when I’m strolling in the park. Though I’m not sentimental by nature, I can’t help feeling that I’m actually in Okinawa. If the park vegetation is slightly unruly or the color of the pond is moss green, it definitely is Okinawa. And in the winter, melting ice on the pond reflecting the bare trees is a Japanese esthetic."

As documented in the Okinawa Prefectural Museum in Naha, Okinawa's principal city, from 1429 to 1609 the Kingdom of Ryukyu thrived on the Okinawan Islands. Ryukyu was a center for maritime trade between China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and the countries of East and South East Asia. This special status persisted even after Japan closed down virtually all other trade.

Like the exuberant vibration of the music of Sanshin, the tea screen binds fine art and daily life in a unity rooted simultaneously in ancient imagery and contemporary world. Jashiki's fabric paintings enlist classic imagery to imply modern and contemporary simplicity. |

|

Untitled, 14 x 46 inches, pigment print on canvas, 2012 |

|

Blue Plaid hangs on the north wall of the lobby of the Hilton Okinawa, which was built right beside the Pacific Ocean. Red Plaid graces the south side of the lobby. Because of oversize windows, Red Plaid shimmers with the orange resonance of the reflection of the sunrise and sunset, while Blue Plaid harmonizes with daytime views of the Pacific. The compositions are simple, and the artist has evinced a high degree of skill in blending of idealization and realistic sternness to achieve an abstract likeness that expresses not only the indomitable air expected of an accomplished artist, but also those more personal traits that reverence his family home. It is nowadays increasingly difficult to distinguish national boundaries. In Hampton, the dazzling outrageous waves crest and break on the silk canvas. And in the silk screens Nice, South France and Untitled, Jashiki realizes phenomena by a stray shaft of ocean and sky light coming through sheer veil spilled over the silk screen. The restriction to horizontal or vertical strokes in Blue Plaid and Red Plaid echoes the image edge. As a result, his work has greater richness of texture and shading than could be achieved simply by depth of color and suggests the interplay of gradient and linearity. Western abstraction has been achieved with Zen-like simplicity, by means of a masterly use of materials. Jashiki’s art is the supreme rebuttal to Greenberg’s dismissal that Minimal Art is “too much a feat of ideation and not anything else.” [6]

Minimal painting still has all the elements of composition and structure and creativity and form according to Frank Stella. [7] In Jashiki's work, "nothing is minimal about ... the craftmanship, inspiration, and aesthetic stimulation" as John Perrault points out. [8] Whether in painting, curtain, tryptic, or screen, Jashiki creates both realistic and highly abstract motifs to covey a romantic feeling. as the artist notes " [in fashion] there are so many contrasts and uses of those elements coexist harmoniously. Eastern/Western, traditional/modern, fine art/commercial design, hand work/high tech (CAD). The interplay of those elements is my chronicle as well." |

|

Blue Plaid, 56 x130 inches, pigment on the canvas, 2011 |

| Red Plaid, 57 x130 inches, pigment on the canvas, 2011 |

| Water, 40 x 60 inches, silk noren, 2017 |

|

However ardently some partisans may advocate for Okinawan independence, it has been almost half a century since the United States formally returned the islands to Japanese control, and Japanese influence is pervasive there. So, it is quite natural that Jashiki's art should celebrate Japanese aesthetic ideals such as pristine elegance, painstaking craftmanship, and celebration of nature's beauty. American appreciation for Japanese culture long pre-dated the battle of Okinawa and the Second World War. During the 1860s, the initial period of "Japan Fever" sparked the US to ratify a trade and friendship treaty with Japan. The 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia exposed the broad public to Japanese artifacts and spurred industrial promotion of Japan. "[A]appreciation of Japanese art encompassed both its own aesthetic merits and its effect on the industrial revolution" [9] and later in the 19th century more and more Americans more became familiar with Japanese culture and objects. In fact, as usual, art appreciation preceded the elevation of Japonisme to “a truly worldwide status [through] commercial negotiations (sometimes among several nations), trade agreements and political machinations and pressure, combined with the personal energy of two generations of entrepreneurs" [10] |

|

| Woods in snow, Central Park, linen folding screen, 120 x 73 inches, 2014 (Details and whole screen)

|

|

Unlike the French and English passion for Japanese art, the initial American enthusiasm for Japanese art owed very little to the wood print, the photograph, or indeed any works on paper [11]. However, in due course the American craze for Japanese art objects would become more comprehensive.

Jashiki's work is eclectic in topic, falls into many different categories, and has evolved beyond any particular philosophical school. It raises craftmanship to the highest level of art. It participated in the artistic revival of naturalism, and on the silk print, in turn was impacted by it. Its meaning and structure acted as a stimulus in his personal drive toward abstraction.

-- Luchia Meihua Lee, Curator

Notes: * The first island chain refers to the first chain of major archipelagos out from the East Asian continental mainland coast. Principally composed of the Kuril Islands, Japanese Archipelago, Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan (Formosa), the northern Philippines, and Borneo; from the Kamchatka Peninsula to the Malay Peninsula. *https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_island_chain**Rewoven: innovative Fiber Art exhibition catalogue, TAAC, QCC Art Gallery/CUNY, Godwin Ternbach Museum/CUNY, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Art, 2017

[1] The Kingdom of Ryukyu existed from 1429 to 1879; it lost its independence in 1609 after invasion and subsequent domination by Japan, but Okinawa was not formally absorbed into Japan until 1879. Thus Okinawans had been Japanese citizens for barely two generations at the outbreak of World War II. Nevertheless, in the wake of the battle of Okinawa, the United States severed Okinawa from Japan after the war and occupied it until 1972. [By comparison, the American occupation of mainland Japan ended in 1952.] During this period, American bases utilized as much as 80% of the available land in Okinawa, the American dollar was the official currency, and vehicular traffic drove on the right. Currently, there are approximately 25,000 American troops stationed in 30 bases in Okinawa. [2] Lee et al, catalogue for Rewoven: Innovative Fiber Art, QCC Art Gallery/CUNY, Godwin Ternbach museum/CUNY, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Art, Taiwanese American Arts Council, 2017, p 110 [3] Ibid. [4] Robert Sokolowski, Introduction to Phenomenology, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p.4 [5] Ibid, p. 11 [6] Edward Strickland, Minimalism: Origins, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1993, p. 273 [7] Gregory Battcock, ed. Minimal Art, University of California Press, 1968, p. 180 [8] "Minimal Abstract by John Perreault", in Gregory Battcock, ed. Minimal Art, University of California Press, 1968, p. 260 [9] Julia Meech and Gabriel Weisberg, Japonisme Comes to America, Harry Abrams Inc., New York, 1990, p.17 [10] Ibid, p. 18 [11] Ibid, p. 19 |

|

Indian summer, 40 x 60 inches, silk tapestry, 2014

|

| Hiroshi Jashiki Hiroshi Jashiki is a textile artist who was born in Okinawa. Growing up in this semi-tropical, amazingly diverse island, his interests in arts and crafts, and international cultural sense came naturally from his earliest years. Jashiki went to Ryukyu University in Okinawa where he studied arts and traditional crafts including hand woven textiles. Later he studied at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where he received his MFA in Fiber Art. Jashiki moved to NY and worked in the fashion industry as a textile designer for 20 years. In 2006, he became an independent textile artist creating original print and handwoven pieces for shows and for public spaces. In his print work, Jashiki employs textile software as a tool to create images inspired by nature, Okinawa, and New York City among other influences. He has exhibited his work in US and Japan; some of the galleries include Cranbrook Art Museum in Michigan, Renaissance Fine Art, Nippon Club New York, and in Japan, Shibatacho Gallery Osaka, Kasagi Gallery Kamakura, Okinawa Contemporary Art Museum, and Atos Gallery.

His latest project is a series of prints for Rihga Royal Gran Hotel, Hilton Okinawa Chatan Resort, Blossom Naha in Okinawa, Courtyard Marriott Tokyo Station, and Ashiya Bay Court club Hotel Resort in Kobe, Japan. |

|

Okinawa (Ryukyu Kingdom) - historical foundation for modern culture |

|

The Government of the Ryukyu Islands was the self-government of native Okinawans during the American occupation of Okinawa. It was created by proclamation of the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands on April 1, 1952 and was abolished on May 14, 1972 when Okinawa was returned to Japan, in accordance with the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement. The government consisted of an executive branch, a legislative branch, and a judicial branch. Members of legislature were elected. The legislature made its own laws, and often had conflicts with USCAR, who could overrule their decisions.(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Ryukyu_Islands) |

|

Naha city, Okinawa, view from Shuri Castle, a Ryukyuan gusuku castle, Okinawa Prefecture Museum. photo 2018 by LL |

| Shuri Castle's seiden (main hall) in 2016. In 2000, Shuri Castle was designated a World Heritage Site, as a part of the Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu. On the morning of 31 October 2019, the main courtyard structures of the castle were destroyed in a fire. photo credit: LL |

| Okinawa traditional lion guard. Those with an open mouth suggest combatting evil from outside. Those with a closed mouth are traditionally related to keeping good spirits inside. Only one is permitted on the rooftop. photo credit: LL |

|

Nice, South France 03, 120 x 70 inches , six-panel silk folding screen, pigment print on silk, wood frames, 2014 |

|

Hiroshi Jashiki artist statement My encounter with local textile was an affair. Although Okinawan textiles play an important role in Okinawan History, my meeting with “it” was not until my late teens, specifically on one afternoon in Shuri High School. I was helping textile major students get ready for their graduate exhibition. I noticed first the smell of Ryukyu Indigo, and then the softness of handspun silk, and last modern geometric patterns. The experience was emotional. “Falling in love” maybe. Not like lovers but like a baby meeting its mother for the first time. I felt warm and protected just by touching the fabric. The affair left an imprint on me. A recent boom in tourism has pushed developers to carelessly build luxury condos, high-end hotels and malls in Okinawa. Eventually booms bust; you can’t count on them in the long run. The flipside--we gain little or nothing culturally. Okinawans pay less attention to their cultural assets in terms of “old” under the circumstances. The Islands have abundant cultural assets: textiles, pottery, music, dance, and more. They’re beautiful, shape our identity and make us different from the rest of Japan and the world. Cultural assets also are a power to share with the global community. And eventually they will help the Okinawan economy. There is no “old “or “new” in cultural assets. They are timeless. They just need close attention, nurturing, and helping hands to evolve with time. That is the reason I use textile medium and an Okinawan aesthetic in my art. |

|

Ruby Plaid, 12 x 12 inches, pigment print on canvas with resin coating, 2011 |

| Summer, 12 x12 inches, pigment print on canvas with resin coating, 2014 |

| Broadway Nights, 15 x 15 inches, pigment print on canvas with resin coating, 2011 |

|

More information about artist Hiroshi Jashiki

Internet Profiles

Hiroshi standing in front of Red Plaid in the lobby of the Hilton Hotel, Okinawa, 2019 |

|

Contact: info@taac-us.org if you are interesting to support this artist in any creative way. |

|

![Image above: Crying in the rain, Ink on book page, 7 1/2 x10 in, 2014~2019, Courtesy of the artist]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiTTP0CxIvvKYtBW02Wg8280m-nPVltFzAZUeI03UkPR4mjewSVTG0Mq8VFy5ewbKULp98CnRRN6oeUX3hS5XQs39g9vgPWTSwCLtH0C51M5-cSDI4NdliglGT6tgA4rhtkWfqiwMcxyi0/w320-h238/No08.jpg)