Why Bird?

Wings to effortless historical consciousness

artist to watch: Sarah Haviland -Why Bird https://conta.cc/2F3tAmt

Sarah Haviland creates art that is drawn from the secret recesses of beings to remind us of a root that must never be forgotten. Nuanced humanism and naturalism condition her experience and expression, both domestically and internationally. A Fulbright scholar and multi-talented artist, she flew from the US to reside in Taiwan in 2019 where she taught art and examined temples: rites, architecture, and tradition. Her global research journey produced an artist book of collages that she created to document her artistic and scholarly sojourn in Taiwan.

Here forbearance, I would never attempt or wish to reduce "the notion of mystery in our visual experience and art representation and dissolve the difference between word and image,"[1] or in this case between the various bird images and their allegorical background in an art historical word sense. As Wittgenstein [2] points out, the dichotomy in the famous duck-rabbit image is only available to those able to coordinate pictures and words, visual experience and language. Sarah Haviland's magnificent wings constitute her signature art form, and are not solely an embodiment of her abstract quality but also carry the revived spirit of symbolic sculpture.

With the above remarks firmly in mind, let us disclose the background genealogy of Sarah Haviland's contemporary art, in which she has broken free from complexity in history, ideology, and philosophy to hone in on the essence of visual media and technology. The role of animals in allegory is a journey though art historical relevance by way of symbols, attributes and personification. In early Christian art birds "suggested the 'winged soul' or the spirit, recalling an idea held by the ancient Egyptians that the soul left the body as a bird at death" [3]. One might further appeal to the likeness of the constructed bird image - in effect, the portrait bird - with the female figure in Haviland's earlier works. Her more recent work pursues a more canonically universal cultural aesthetics, where we can find the transformation from an intricate self-consciousness and mental cultivation towards a pronounced outward coordination with the natural environment. The practicality of furniture is invited to flight by wings which appear unexpectedly but organically from the sofa or chair to embrace the sitter. Carrying this idea to its logical conclusion, a chair has been placed up a tree where it hangs in the air. Haviland explored the interstice between angels, birds, and humans in a spectacle of light at the Flatiron Building in Manhattan. She has disentangled from the historical context.

Haviland, in her recurrent use of metal mesh as a material, employs the net, which of course is a contrivance to trap birds. Yet in Haviland's art, metal mesh is porous and airy, and thus has a degree of lightness and effortlessness. Hence, the inorganic participates in implied natural flight, and points indirectly towards human flight. Haviland's birds carry a different character; she captures the emotional effect of transforming sumptuous feather and ornament to simplicity of form. At the same time, the complexity of her art displays the nuances of the translucent web and the air within. Her longing has landed on the grass lawn and turned into an owl perched in a tree and holding a globe.

Moving to a contemporary theoretical view of the subject in general, the form of these winged creatures seems to create a self-understanding within experience in human society. In Foucault's words, three types of technique may be singled out; those that permit one to "produce, to transform, to manipulate things" [4] and it is by the tranformative techniques that a sign system can be revealed in the conduct of individuals. As Foucault remarks, it is the techniques or technology of the self in operation on our own body, mind and thought, which permits individuals to "transform themselves, modify themselves, and to attain a certain state of perfection, of happiness, of purity, of supernatural power, and so on... "[5]. Sarah Haviland brings these meaningful subjects across history and leads to modern concerns and a contemporary accomplishment.

It is impossible not to acknowledge the ever-present birds in Haviland's art and the profound impression made upon the artist by her two sojourns in Taiwan. It is no accident that Chinese mythology (in the Classic of Mountains and Seas) talks about a fabulous creature with the body of a bird and human face. The great beauty of the peacock, with its lavish, and decorative plumage, was a favorite subject for artists throughout the ages. As a token of Juno, it was useful in allegory. The ever-vigilant, powerful eagle was associated with Jupiter "because of its great strength, speed and soaring flight." [6], as the winged lion symbolizes Saint Mark, because the lion represents strength, courage and fortitude, and as a result has long been a royal and aristocratic emblem.

In Chinese mythology, the immortals ride on cranes. Inspired by local folk culture in Taiwan as expressed in temple motifs, Haviland locates this idea by referring to egrets - a frequent sight in Taiwan associated with its favorite locales: the rice field or on the water buffalo's back. She then appeals to the fact that egrets are migratory to suggest that the rider is migratory as well.Turning to the rider, women are associated in Chinese culture with the phoenix, the five-colored bird of wonder. Often used to stand for auspiciousness, it also symbolizes longevity and resurrection (in many cultures, it was supposed to die and be reborn in fire), and appeared in Egyptian mythology as the eternal "Bennu phoenix"; (modeled in fact upon a large heron; but to complete the circle, egrets are a type of heron). It was associated with the sun god and the periodic inundation of the Nile. And thus it was associated with the first inundation that gave birth to the world, from which the bird also symbolized time. The Bennu bird was also linked with Osiris, god of the underworld and of resurrection [7]. The legendary phoenix was also "known" through Herodotus to the Greeks.

Despite the subtext of allegory and historical tradition, I would insist upon the social dimension of Haviland's iconography. Her art is inseparable from environmental concern but in no way subsumed by it.

Notes:

[1] Nelson, Robert S. and Schiff, Richard, Critical Terms for Art History, University of Chicago Press, 1996, pl 49

[2] Wittgenstein, Ludwig philosophical Transactions Translated by G.E.Em Anscombe, Blackwell, 1953

[3] Carr-Gomm, Sarah,The Secret Language of Art, Duncan Baird Publishers, London, 2008, Symbols and Allegories, p. 239

[4] Carette, J. R., Religion and Culture: Michel Foucault, Routledge, 1999, p. 161

[5] Ibid, p. 162

[6] Carr-Gomm, Sarah,The Secret Language of Art, Duncan Baird Publishers, London, 2008, Symbols and Allegories, p. 36

[7] Hart, George. A dictionary of Egyptian gods and goddesses. Routledge & Kegan Paul. 1986. ISBN 0415059097. http://www.egyptianmyths.net/phoenix.htm)

https://conta.cc/2F3tAmt

We hope your interest is piqued and you do not begrudge praise and admiration. |

|

Escaping from the interference of human limits, we know access to the arts is intrinsic to a high quality of mind, thought and body in our life at any moment.

Sarah Haviland creates art that is drawn from the secret recesses of beings to remind us of a root that must never be forgotten. Nuanced humanism and naturalism condition her experience and expression, both domestically and internationally. A Fulbright scholar and multi-talented artist, she flew from the US to reside in Taiwan in 2019 where she taught art and examined temples: rites, architecture, and tradition. Her global research journey produced an artist book of collages that she created to document her artistic and scholarly sojourn in Taiwan.

image above: Migration Map, Arc Notebook 20. From Arc of the Moral Universe Notebook Project

|

|

Aerie, 2010. Expanded steel, wire mesh, rebar, stone, 96” x 72” x 36 ” Ossining High School, NY

Constructed for a site overlooking the Hudson River Valley, Aerie combines natural and architectural forms in monumental mesh. The sculpture’s base echoes a landmark bridge, while the figure of a nesting eagle refers to the revival of the river and the famous local bird, recalling national and multicultural myths, environmental treasures, and the human desire to fly. |

|

Why Bird? Wings to effortless historical consciousness |

|

Here forbearance, I would never attempt or wish to reduce "the notion of mystery in our visual experience and art representation and dissolve the difference between word and image,"[1] or in this case between the various bird images and their allegorical background in an art historical word sense. As Wittgenstein [2] points out, the dichotomy in the famous duck-rabbit image is only available to those able to coordinate pictures and words, visual experience and language. Sarah Haviland's magnificent wings constitute her signature art form, and are not solely an embodiment of her abstract quality but also carry the revived spirit of symbolic sculpture.

With the above remarks firmly in mind, let us disclose the background genealogy of Sarah Haviland's contemporary art, in which she has broken free from complexity in history, ideology, and philosophy to hone in on the essence of visual media and technology. The role of animals in allegory is a journey though art historical relevance by way of symbols, attributes and personification. In early Christian art birds "suggested the 'winged soul' or the spirit, recalling an idea held by the ancient Egyptians that the soul left the body as a bird at death" [3]. One might further appeal to the likeness of the constructed bird image - in effect, the portrait bird - with the female figure in Haviland's earlier works. Her more recent work pursues a more canonically universal cultural aesthetics, where we can find the transformation from an intricate self-consciousness and mental cultivation towards a pronounced outward coordination with the natural environment. The practicality of furniture is invited to flight by wings which appear unexpectedly but organically from the sofa or chair to embrace the sitter. Carrying this idea to its logical conclusion, a chair has been placed up a tree where it hangs in the air. Haviland explored the interstice between angels, birds, and humans in a spectacle of light at the Flatiron Building in Manhattan. She has disentangled from the historical context. |

|

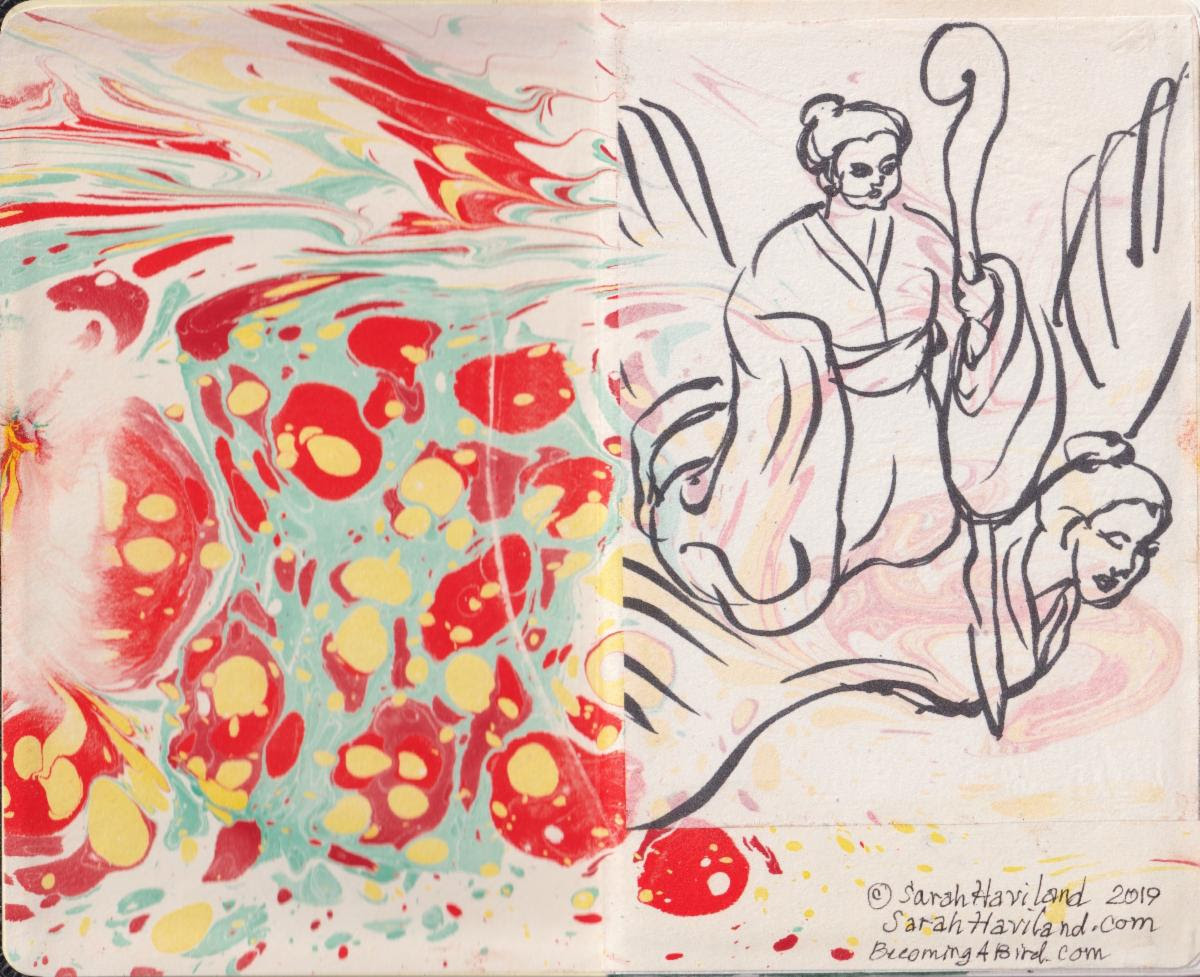

Why Birds? Arc Notebook 11. From Arc of the Moral Universe Notebook Project 2019, Paper collage, 8” x 10”

From a series of double-spread journal collages, Why Birds? reflects on Sarah Haviland's bird-figure research pursued in Taiwan. The Arc of the Moral Universe: A Notebook Project is a collaborative project organized by artist Carla Rae Johnson responding to challenging times by keeping a visual journal (July 4, 2018-July 4, 2019). A new notebook project, Arc of the Viral Universe, is ongoing. |

|

Owl in Wonderland 2017 Wire mesh and mixed media 40”x60”x20” Saunders Farm, Garrison, NY

Owl in Wonderland continues the series of human-bird hybrid figures made in transparent wire mesh that point to our essential connection to nature. It was inspired by an encounter with an owl in a tree at dusk. In New York State the short-eared owl is an endangered species. The piece was installed with the collective Collaborative Concepts on a farm in the lower Hudson Valley. |

| In the Balance 2016 Galvanized mesh, recycled metal chair, laminated photo 36”x36”x12” Saunders Farm, Garrison, NY

Following a series of functional winged benches and seats, In the Balance offers a more tenuous presence. A child-size silver chair with metal-mesh wings is suspended in the trees, bringing another perspective to awareness of the world around us. Here the seat of consciousness bears our earth’s round blue-and-green image. |

|

Haviland, in her recurrent use of metal mesh as a material, employs the net, which of course is a contrivance to trap birds. Yet in Haviland's art, metal mesh is porous and airy, and thus has a degree of lightness and effortlessness. Hence, the inorganic participates in implied natural flight, and points indirectly towards human flight. Haviland's birds carry a different character; she captures the emotional effect of transforming sumptuous feather and ornament to simplicity of form. At the same time, the complexity of her art displays the nuances of the translucent web and the air within. Her longing has landed on the grass lawn and turned into an owl perched in a tree and holding a globe.

Moving to a contemporary theoretical view of the subject in general, the form of these winged creatures seems to create a self-understanding within experience in human society. In Foucault's words, three types of technique may be singled out; those that permit one to "produce, to transform, to manipulate things" [4] and it is by the tranformative techniques that a sign system can be revealed in the conduct of individuals. As Foucault remarks, it is the techniques or technology of the self in operation on our own body, mind and thought, which permits individuals to "transform themselves, modify themselves, and to attain a certain state of perfection, of happiness, of purity, of supernatural power, and so on... "[5]. Sarah Haviland brings these meaningful subjects across history and leads to modern concerns and a contemporary accomplishment. |

|

Black Kite Bench, 2015. Bamboo, sisal, fishing float, 60" x 72" x 36" National Museum of Marine Science & Technology, Keelung, Taiwan Curated by Jane Ingram Allen

Black Kite Bench was one of eight international public artworks selected by curator Jane Ingram Allen for an environmental residency at the National Museum of Marine Science & Technology in Keelung, Taiwan. The functional bench was built with environmental materials and traditional methods of bending and binding bamboo, in order to call attention to preservation of ocean life. |

|

Trio 2001 Bronze 108”x91”x76” Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, NJ Commissioned by the Sculpture Foundation, Trio is a unique bronze cast on permanent installation at Grounds for Sculpture, New Jersey’s premier sculpture park. The nine-foot piece was scaled up from a one-foot clay model by computer scanning and milling, then reworked by hand. It suggests a tree, a hand, or intertwined female figures, and recently inspired three dancers to collaborate on choreographing a new work called “Paths.” |

| Sarah Haviland

Living in the lower Hudson Valley and working there and in New York City, Sarah Haviland earned a BA with Distinction in Art from Yale and an MFA in Combined Media from Hunter College. Her abstract and figurative sculpture and public art installations have been exhibited widely both in the U.S. and internationally. She pursued her twin interests in art and art education as a Fulbright Scholar in Taiwan in fall 2018. In 2015, she was selected for and participated in an international environmental residency in Keelung, Taiwan. Her sculptural work includes commissions at NYU Langone Medical Musculoskeletal Center, NYC; Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY, NYC; Seven Bridges Foundation, Greenwich, CT; Pratt Sculpture Park, Brooklyn, NY; Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, NJ; Rockland Center for the Arts, West Nyack, NY; and the National Museum of Marine Science and Technology in Taiwan. She will have a solo exhibition in 2021 at the Hammond Museum, North Salem, NY. She has had residencies at Sculpture Space, Skowhegan, and Yaddo.

She teaches art at Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY, and taught at Taipei National University of the Arts.

|

|

Rise Above 2017. Steel, galvanized mesh, lights 10’ x 11’ x 6’ triangular window installation Flatiron Prow Art Space, NYC Curated by Cheryl McGinnis

The illuminated installation Rise Above, designed for display in Manhattan’s Flatiron Building with city views on three sides, was intended to project hope and female energy. It presents five winged figures in wire mesh that explore human-bird personae. These soul-images acknowledge dualities: strength and subtlety, movement and stability, ancient and contemporary, earth and sky. |

| I Saw the Wind Within Her 2010 Steel and wire mesh 72” x 96” x 48”

Created to float above empty spaces indoors or out, I Saw the Wind Within Her combines human, natural, and supernatural references in recognition of the forces around us. The open steel-and-mesh frame appears suspended like an airborne spirit, suggesting both presence and absence. The title comes from Emily Dickenson’s poem no. 1502.

|

|

It is impossible not to acknowledge the ever-present birds in Haviland's art and the profound impression made upon the artist by her two sojourns in Taiwan. It is no accident that Chinese mythology (in the Classic of Mountains and Seas) talks about a fabulous creature with the body of a bird and human face. The great beauty of the peacock, with its lavish, and decorative plumage, was a favorite subject for artists throughout the ages. As a token of Juno, it was useful in allegory. The ever-vigilant, powerful eagle was associated with Jupiter "because of its great strength, speed and soaring flight." [6], as the winged lion symbolizes Saint Mark, because the lion represents strength, courage and fortitude, and as a result has long been a royal and aristocratic emblem. |

|

Living in Taipei, Arc Notebook 1 From Arc of the Moral Universe Notebook Project |

| We the People, Arc Notebook 9 From Arc of the Moral Universe Notebook Project |

|

In Chinese mythology, the immortals ride on cranes. Inspired by local folk culture in Taiwan as expressed in temple motifs, Haviland locates this idea by referring to egrets - a frequent sight in Taiwan associated with its favorite locales: the rice field or on the water buffalo's back. She then appeals to the fact that egrets are migratory to suggest that the rider is migratory as well.Turning to the rider, women are associated in Chinese culture with the phoenix, the five-colored bird of wonder. Often used to stand for auspiciousness, it also symbolizes longevity and resurrection (in many cultures, it was supposed to die and be reborn in fire), and appeared in Egyptian mythology as the eternal "Bennu phoenix"; (modeled in fact upon a large heron; but to complete the circle, egrets are a type of heron). It was associated with the sun god and the periodic inundation of the Nile. And thus it was associated with the first inundation that gave birth to the world, from which the bird also symbolized time. The Bennu bird was also linked with Osiris, god of the underworld and of resurrection [7]. The legendary phoenix was also "known" through Herodotus to the Greeks.

Despite the subtext of allegory and historical tradition, I would insist upon the social dimension of Haviland's iconography. Her art is inseparable from environmental concern but in no way subsumed by it.

-- Luchia Meihua Lee, Curator

Notes: [1] Nelson, Robert S. and Schiff, Richard, Critical Terms for Art History, University of Chicago Press, 1996, pl 49 [2] Wittgenstein, Ludwig philosophical Transactions Translated by G.E.Em Anscombe, Blackwell, 1953 [3] Carr-Gomm, Sarah,The Secret Language of Art, Duncan Baird Publishers, London, 2008, Symbols and Allegories, p. 239 [4] Carette, J. R., Religion and Culture: Michel Foucault, Routledge, 1999, p. 161 [5] Ibid, p. 162 [6] Carr-Gomm, Sarah,The Secret Language of Art, Duncan Baird Publishers, London, 2008, Symbols and Allegories, p. 36 |

|

| Passage, Arc Notebook 1 From Arc of the Moral Universe Notebook Project |

|  |  | Woman Riding an Egret, small 2019 Steel, wire mesh 24”x16”x16”

Woman Riding an Egret is inspired by images of flying Immortals in China and Taiwan. This representation of heavenly transit evolved from ancient bird-deity themes and is still a familiar reference to the afterlife. The bird here is an egret, which, like the crane, connotes good fortune and is often seen in Taiwan. |

|  |

|

Migration Myths: Woman Riding an Egret 2019 Steel, wire mesh, recycled plastic bags 72”x84”x70”

Woman Riding an Egret derives from Taoist images of flying Immortals found in Taiwanese temples. The bird-vehicle is a monumental egret. Like many migrants, the traveling female figure wears a backpack. Migratory birds and migrating humans can both be considered endangered today. |

|

Moche Bird-Runner, 2020. Steel, wire mesh, enamel 62” x 30” x 36”

Moche Bird-Runner is based on a small mosaic earring showing an ancient Peruvian bird-man. The running figure with beak and wings also appears in Moche red pottery, but in the mosaic, he’s depicted in vivid color like a modern superhero. Today, when caravans of immigrants from Latin America seek refuge at the US border, this figure seems a poignant vision. |

| Deep Song, 2018. Wire mesh, enamel paint, found objects, 75" x 48" x 35"

Deep Song belongs to Haviland's “Aviary” series of sculptures that combine bird-figures, birdcage structures, and symbolic or votive objects. This piece, with reference to the Spanish Cante Jondo style, was made after the election of 2016 and shows a black bird spreading its wings over a tilting house-shaped cage, inside of which hangs a snarl of line with crystal drops. |

|

Copper Beech: People’s Trust, 2003. Copper mesh, steel, mirror, wood, paint, silk, photos 25’x28’x58’ room installation (Tree 16’ tall) Grand Banking Room, The Arts Exchange, White Plains, NY Copper Beech: People’s Trust was commissioned by Westchester Arts Council, with an NEA Creativity Grant. This atrium-scaled installation was designed to complement the original bank’s 1930’s architecture with coffered ceiling, as well as pay tribute to a historic landmark, a copper beech tree saved from destruction by civic efforts during urban renewal in White Plains. |

|

More information: SARAH HAVILAND PO Box 178, Crompond, NY 10517

Internet Profiles

Sarah Haviland in the Studio, 2019

|

|

Contact: info@taac-us.org if you are interesting to support this artist in any creative way. |

|

No comments:

Post a Comment